Colleges routinely fail to ask about new hires’ history of sexual harassment

Tips

Susan Fortney, Texas A&M University and Theresa Morris, Texas A&M University

When three graduate students sued Harvard University in early 2022 for sexual harassment by a tenured professor, they claimed the school hired the professor despite knowing that he allegedly harassed students at the last school where he worked.

The students also claim Harvard ignored the professor’s sexual harassment of students at Harvard, including one of the individuals who sued. Their lawsuit also alleges the school ignored how the professor allegedly retaliated against them.

Such allegations may leave students, parents and the general public wondering if colleges and universities take the issue of sexual harassment seriously.

As a sociologist and a law professor who study how to prevent sexual harassment and misconduct in higher education, we know that colleges and universities generally recognize sexual misconduct as a major problem. However, they also tend to focus more on compliance with laws related to sexual misconduct than on prevention.

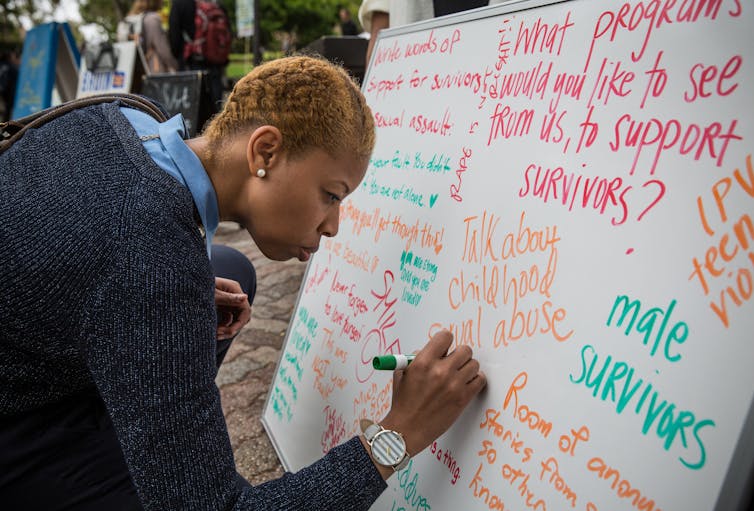

We think sexual harassment on campus, which affects nearly half of all students, could be better averted if more colleges improve how they screen applicants. It’s a measure that some universities and at least one state are beginning to require.

Colleges spend hundreds of millions of dollars to address sexual harassment. But they usually do not screen prospective hires for prior sexual misconduct.

This gives rise to a phenomenon known as “pass the harasser.” The phrase generally refers to how institutions enable employees to move on to new jobs without their new employers ever finding about their history of sexual harassment in the workplace.

Failure to investigate

Pass-the-harasser situations may arise when hiring schools do not seek or investigate information related to past sexual misconduct.

In the rare event that hiring schools proactively seek information, they may hit a brick wall when the contacted school refuses to provide information. Such refusals may come down to a school’s self-interest. For instance, the candidate’s current school may want the employee to land another job. This can be especially true if the person has the relative job security of tenure, which can make it harder for schools to fire them. University officials may also decline to share information because they fear accusations of defamation or other claims.

One higher education newspaper called the pass-the-harasser phenomenon “higher ed’s worst kept secret.” Some universities are changing personnel practices to address the concern of employees changing jobs with little or no scrutiny related to their past sexual misconduct.

A new way to hire

For example, the University of Wisconsin System will now automatically share information about sexual harassment findings against employees when contacted for a reference check by another system campus or state agency. The system also requires that references and final candidates answer certain questions. Those questions include whether the candidate was ever found to have engaged in any sexual violence or sexual harassment. They also ask whether the candidate is currently under investigation or left employment during an active investigation in which the person was accused of sexual harassment.

The policy changes were made after it came to light that a campus administrator at one school in the Wisconsin system had resigned during an investigation into sexual harassment. That investigation eventually found he had likely harassed someone on campus, only to be hired at a different system school two years later. The case was particularly noteworthy because the employee had been hired as assistant dean of students and deputy Title IX coordinator – the same position he held when he resigned. Title IX coordinators are responsible for coordinating investigations into sexual misconduct cases on campus.

Under the Wisconsin system, job applicants are asked to sign a release authorizing former and current employers and references to release information related to the applicant’s employment record.

Although laws vary, such releases provide consent to disclosure. They also provide a defense in case schools get sued for improper disclosure of employee records.

In 2019, the University of California Davis also implemented new hiring measures. These new measures include reference checks that specifically ask about sexual misconduct.

The procedures require all applicants for tenured and continuing lecturer positions to sign a release for substantiated findings of misconduct, including sexual assault and harassment.

Building on the steps taken by UC Davis and the University of Wisconsin System, Washington became the first state to enact legislation to deal with pass-the-harasser concerns. Beginning July 1, 2021, Washington law requires that postsecondary schools request that a job applicant’s current and past postsecondary employers disclose any sexual misconduct committed by the applicant. Prior to an official offer of employment, colleges must ask applicants whether they were found to have engaged in sexual misconduct anywhere they have worked. They must also ask whether the applicant is being investigated for sexual misconduct or left their job during an investigation.

Further, this law requires postsecondary schools in Washington to disclose substantiated findings of sexual misconduct to any employer doing a reference or background check. In other words, the hiring school has to ask about an applicant’s past sexual misconduct, and the school where the applicant works has to answer.

Finally, the law requires that investigations be completed with written findings, unless the victim requests otherwise. This prevents the employee from resigning to avoid findings of misconduct. Notably, the law does not permit nondisclosure agreements that prohibit disclosure of sexual misconduct findings.

More recently, on Nov. 1, 2021, the Association of American Universities, an organization of the top 66 research universities, adopted a set of principles meant to encourage its members to do more to prevent sexual harassment. Three principles directly deal with sexual misconduct findings and investigations.

First, a member school should request or require applicants to sign a release for prior findings of sexual misconduct. Second, schools should share substantiated findings of sexual misconduct with prospective employers when requested. Third, schools should complete all investigations into sexual misconduct.

Unless colleges and universities across the country adopt similar principles and practices, hiring schools may not be able to find out if the people they are hiring have a history of sexual misconduct.

Also, we believe individuals may be more at risk of being sexually harassed at schools that do not screen candidates. We say this because serial harassers may seek positions at schools where they know they won’t be screened.

To encourage schools nationwide to change their practices, accreditation agencies – the organizations that ensure schools meet certain standards – could adopt a standard covering personnel inquiries related to misconduct findings. Accrediting agencies could require schools to do more to find out if an applicant has a history of sexual misconduct. Schools that fail to do so could lose their accreditation.

Such a standard would reinforce that sharing employee disciplinary information is a crucial part of campus security, as well as a shared responsibility within the larger academic community.

These precautions also reinforce the important message that schools proactively address sexual harassment.

[More than 150,000 readers get one of The Conversation’s informative newsletters. Join the list today.]![]()

Susan Fortney, University Professor and Professor of Law, Texas A&M University and Theresa Morris, Professor of Sociology and Women's and Gender Studies and Coordinator of the Women's and Gender Studies Program, Texas A&M University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views and opinions expressed in the article are solely those of their authors, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of DiversityWork.com.

Comments (5)

Best Company Reply

- Ali Tufan

- 2 days ago

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis mollis quam.Because Other Candidates

- Martha Griffin

- 23 August 2018

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis.Aldus PageMaker including versions Reply

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis mollis quam.